A day or two ago I was reading a posting from one of my favourite bloggers, regarding a inexplicably tardy letter to the editor of May 2012 in response to something published in 1986.

It reminded me of an incident from the time when I was working at the Post Office in Gladstone, Q. during the university vacation. It must have been 1968.

At that time, I took any paid employment I could get to supplement my extravagant lifestyle on a stipend while at the University of Queensland, on the $19 per week my Commonwealth Scholarship paid. These jobs included storeman & packer on the Gladstone wharves, bar attendant and wine waiter, and proof-reader for the Gladstone Observer. I was versatile, and poor and, like Rupert Murdoch, not too humble to take anything on.

The last of these jobs was one from which I prevented some quite alarming passages appearing in print, though was unable, for diplomatic reasons, to alter the more purple of prose in the Births, Marriages and Deaths section, popularly referred to as Hatched, Matched and Despatched. I wonder if this terminology is as frequent now as it was a half-century ago?

But back to the Post Office. The GPO in Gladstone had a large letter receiver [that's the real name for the container where you push letters and parcels through the slot to post them]. It was so big I could get inside it easily, and often did in order to reach an item in the corner.

It was said, and knowing some of my colleagues at the PO it could be true, that when little "Chook" Fowler got in there once, they locked him in as a joke and left him there till the Postmaster arrived at 8.30 am. No, I don't believe it, but was pleased that I was the only one there at the time of the incident I am about to relate, or they might give the joke a second run if there were a skerrick of truth in it.

Someone had posted a Christmas parcel plastered with bright stamps to the value of what I assumed was the correct amount. Those were the days when you didn't bother too much about trifles like whether the weight was exactly right to the ounce for the postage stamps on the parcel, unless it was wildly out. It was Christmas, after all. In this case, the package was impressively big for the size of the slot through which it was delivered into the letter receiver.

This rightly evokes images of a somewhat troublesome if successful birth, but the similarity didn't end there. In squeezing it through the slot, the sender set off a battery-controlled baby's cry from a doll in the parcel. I don't know if they knew that had happened, but if they'd posted it the evening before, there wasn't much they could have done about it anyway.

So, when I got to work at 6 o'clock that morning, first on the scene, I was perturbed to hear very strong agitated-baby noises coming from the letter receiver. Well may you imagine the images in my mind of a newborn babe that I was about to find - a Moses perhaps, rather than a Christmas Jesus.

Locating the source of the noise in the semi-darkness of the letter receiver was not all that hard, but I did have to get well inside the box to reach it. Sitting on the floor of the letter receiver, I rather gingerly prodded and poked the parcel to ensure that someone wasn't trying to post a real live baby to Sarah Holmes of Spring Hill, Queensland.

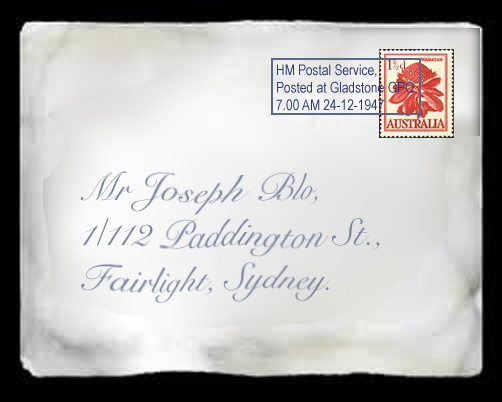

|

| After being squeezed through. |

I did that once or twice more just to be sure, and after leaving it in OFF screaming mode, tossed the parcel into one of the mailbags. I daresay dolly might have spent the entire journey to Spring Hill alternately wailing and sleeping when bumped, unless someone investigated further or her battery gave up the ghost on the Rocky Mail train that night.

But crying dolly was not what I was talking about anyway. When I was sitting inside the letter receiver, my eyes got used to the dark. I looked up for some reason, and saw that a letter was stuck in a crack below and to the side of the opening. No-one would notice it so high up except by sheer chance, as I did. If Chooky Fowler had been locked in there for some time, he hadn't seen it.

Someone must have slipped it through the postal slot, and on the long drop down the letter had speared itself into that crack and was trapped by its corner, and there it had stayed through the years.

I took myself and it out of the letter receiver, and examined it in the light. It had been there a long time. It was greyish and looked like it had almost shrunk. The name and Sydney address, written in a tolerable hand with pen and now-faded ink, were still clearly visible. It had a penny-ha'penny stamp on it.

I suppose I should have waited, and taken it to the Postmaster when he arrived, but I couldn't resist the temptation. I took the manual stamp-canceller - i.e., the rubber stamp that shows time and date of postage, turned the numbers back to the day I was born, and clearly cancelled the stamp. It was perfect. I then turned the manual stamp to the correct date and time, and sorted the letter into its right bundle along with the others for the Sydney mail.

Sad to say, I never heard a thing about that letter again. I was wishing that it became one of those newspaper stories which sometimes get a run in the national press about mysterious letters that turn up out of nowhere. If it did, I didn't see it, though I kept my eyes open for a few days.

Most likely it ended up at the Dead Letter Office, along with those thousands of forlorn missives declaring eternal love and other threats to the intended recipient's equanimity.

But anyway, I do hope Sarah Holmes was happy with her dolly and its frantic newborn wail.